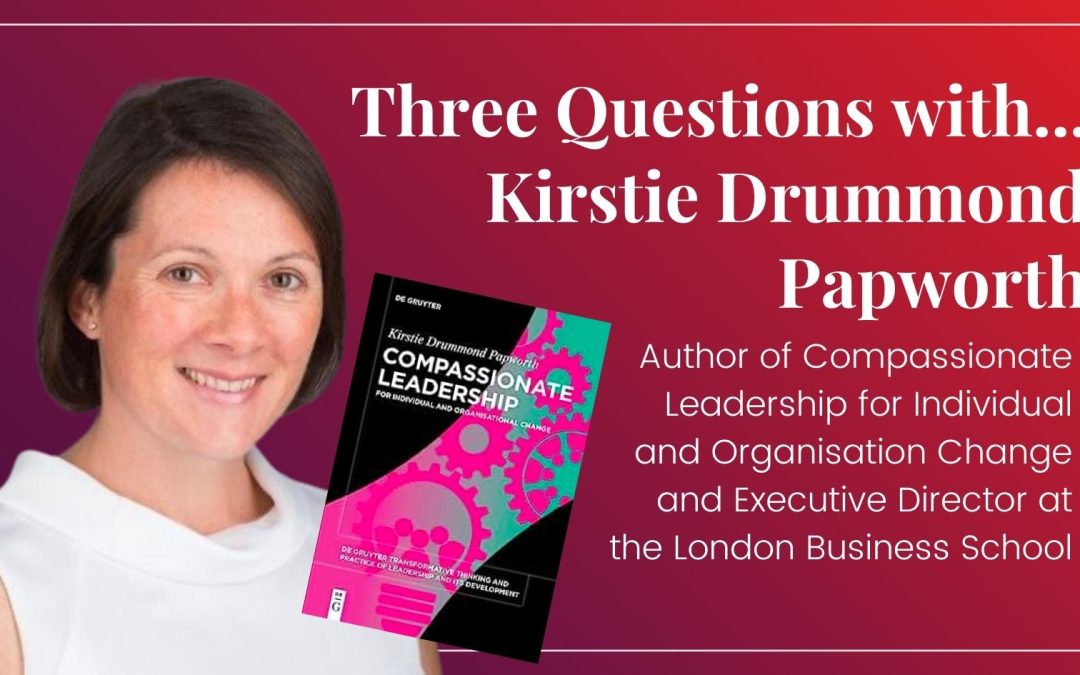

This month we asked Kirstie Drummond Papworth, Executive Director of the London Business School, about her book Compassionate Leadership for Individual and Organisation Change:

Q: Where did you first notice how compassion can be misconstrued?

I was probably consciously aware of compassion’s dubious reputation when I was researching Organizational Compassion and Affective Commitment (or employee engagement) for a Masters Dissertation. As I approached a number of organisations about taking part in the research, one HR Director wrote to her colleague, advising that I should look elsewhere. She suggested that perhaps “a more American or a John Lewis type business might work better where they actually care about their staff” might be a better option. Disappointing, but not entirely a surprise, because I suppose I have subconsciously known that compassion is not universally well regarded for quite some time. There is even a study of newspaper word usage which showed that until the 1990s, words like ‘compete’ or ‘win’ were in abundance while ‘compassion’ was barely used.

This reputation is not just frustrating from an individual researcher’s perspective, it also impacts the organisational bottom line. Compassion is ultimately a commercial decision. People who perceive their organisations and leaders to be compassionate are less stressed and less prone to burnout, as well as more engaged, more involved in prosocial acts at work, and more likely to stay with the organisation.

Especially in organisations, compassion is not a weakness. It bolsters the resilience of leaders and those around them, and – according to one study on airline outcomes post-9/11 – can even be a significant predictor of company survival. Compassion’s reputation is a little unfair, to say the least.

Q: What is one lesson that you hope people in positions of power, and those aspiring to be, take from your book?

There are many ways to learn from the book; it is written to be based in research and immediately practical. I suppose the main lesson for those in positions of power would be to start with ourselves. There is a whole chapter on self-compassion, what it is and how to apply it. This may seem uncomfortable in a leadership book, but my Psychology Masters research on the self-reported effects of self-compassion on stress, anxiety and depression in leaders demonstrated that even a few minutes of practice each day can quickly add up to a significant, positive difference. When we experience compassion for ourselves, we will also be more resourced to be able to extend this to other people; those we know, those we do not know, and even those we consider to be our adversaries.

Q: How do you think what successful leadership looks like will change over the next 10 years?

Well, ten years ago I was told that my idea to write a dissertation focused on compassion in organisations was ridiculous, whereas now compassion is becoming increasingly researched and far more acceptable. So hopefully in ten years’ time, successful leadership will have compassion at its core.

The definition of leadership success is already changing. We care less about what position someone holds, more about how they achieved their success. We care less about how much money someone has, more about how they earned it. And we even care less about how much power someone has, but much more about what they plan to do to support others with their influence.

Future successful leadership, then, will hopefully be a combination of self-compassion and compassion for others, with the wellbeing of our interconnected systems at its core. I do not think this is unrealistic or idealistic. We are all compassionate by nature, it is simply that the twists and turns of our individual life histories have dented or obscured our access to this nature. Leadership which returns us to our compassionate selves will be the most successful, enduring form of leadership.

Visit www.wibenetwork.com for more information on Women in BizEd.